I've been listening to Seals & Crofts. They had an enormous influence on me at a young age. When I was a kid, we had free access to the entire collection, from Toscanini and Sir Thomas Beecham to Rodgers and Hammerstein to the Kingston Trio and the Four Lads to Crosby, Stills, & Nash and Simon & Garfunkel to Herb Alpert, and on and on. They were all together, roughly categorized, and bursting with strange resemblances to each other.

Moments of sheer musical pleasure abounded: Toscanini's breathless intro to

Traviata, the Kingston Trio's haunting guitar-and-bongos rendition of

They Call the Wind Mariah, Richard Rodgers's sparkling, no-words-needed entrance of the King's children in

The King and I — my ears were tuned to music. I listened obsessively to the way that the pans were assigned on all the Partridge Family albums: bass and kick in the center, toms absurdly panned left to right, backup singers gathered round, acoustic guitar on left, electric on right, keyboards somewhere in back, and David Cassidy just a little to the right of center, every single time. I tried to figure out why Benny Goodman's group almost always stuck a sixth into any chord, minor or major. I wondered over the single 5/4 measure in

Bei Mir, from his Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert: was it an accident? an editing thing? a real, intentional 5/4 measure?

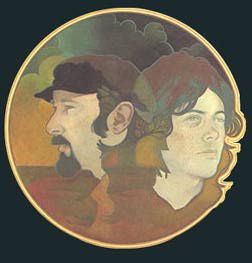

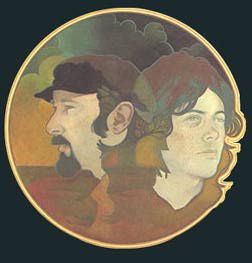

And I listened to Seals & Crofts. Their faces looked out from the album covers, out into the distance, radiating health and integrity and grooviness and wisdom. The hair was long but neat; the beard was trimmed; the music spoke of things important in the late sixties and early seventies, but didn't yell. No doubt drugs were involved, but they weren't trumpeted or celebrated. The lyrics were literate, and often referred to the Baha'i Faith. A line (from

East of Ginger Trees) that quoted from their scripture is never far from my mind: "Be lions roaring in the forest of knowledge, whales swimming in the oceans of life." That struck me, because they seemed to be such masters at everything they touched. Listening to them, I wanted to be remarkable. That very song ends with an insistent, simple rhythm that has threaded its way through my own compositions; I use it whenever I want to symbolize God's calling of us to a new place.

That potent combination of hippie freshness with adult mastery reminds me now of my parents. Looking back on it, how could I have missed this? They reacted to Seals & Crofts because that's who they were. They were a little old, and treasured civilization too much, to have been hippies, but they were hippie sympathizers. I have an image of my dad with long (but neat!) hair, a full (trimmed!) beard, a jacket and turtleneck with a peace symbol prominently hung on leather, standing next to my mom, whose long hair echoed the dramatic drip of green paisley flared pants she was wearing.

I guess most people's knowledge of the duo starts and ends with

Summer Breeze, Diamond Girl, and

Hummingbird, which I just heard in the supermarket 2 different times last week. That may be what kicked this whole thing off. Just the two words "Summer Breeze" say it all. You hear about 12 different voices, perfectly limning a minor-11 chord, with a druggily fuzzy guitar line in the background, surrounded by an orchestra. It sounds summery, breezy, effortless, and relaxed, and yet much more sophisticated than, say, anything Frank Sinatra was doing in 1971.

The Seals & Crofts modus is to take an extremely catchy hook, some insightful but not groundbreaking lyrics (the lyrics to

Summer Breeze are, after all, as close as you're going to get to a hippie tribute to Mirabel Morgan), and a pleasing, roaming melody. They then sing with gentle voices that interlock perfectly: Jim Seals with that odd edge, Dash Crofts with a smoother, boyish voice. After the verses and choruses have lodged themselves, they then embark into new harmonic territory, progressing to a point where the original key is almost lost, and then they deposit you on new harmonic ground that you'd never have expected. You feel as if you've been taken for a delightful ride. It's that harmonic adventure that gives the bridge of

Summer Breeze its breezy lift, and gives

Hummingbird its soaring joy, and

Ginger Trees its groovy

telos. "Where on earth is this going to land?" you think. "Ahhhhh! there."

What wonders can be created, with a horde of superb studio musicians, with two really great leaders holding the baton!